Little did Ralph Steeves know what would be ahead of him when he decided to move to Calgary in 1944. His career in geophysical field services has taken him to places many dream of travelling to and a few you don't want to think about travelling to.

"I'm not a country club cocktail kind of guy," says Steeves, who doesn't let his whirlwind adventures inflate his ego. After all, he's a man who grew up with modest beginnings.

The younger of two children, Steeves was born on December 23, 1926 to a farmer and his wife in Albert County, New Brunswick. "We had in those days what you'd call an organic farm," recalls Steeves. "Buckwheat, maple syrup and fiddle heads."

He attended primary school in Dawson's Settlement. Then the family moved to Salisbury, a small town near Moncton, where he attended elementary and high school. "That was a real big high school," says Steeves with a real straight face. "One room and the same teacher for three years. I graduated from a class of 14." One of a closely-knit bunch, he recently attended the 55th reunion of his high school graduating class.

While in high school, Steeves joined the army cadets and also served the reserve army. It was then when he made his first movie appearance as one of the 30 cadets chosen for a National Film Board feature on cadet life. Upon high school graduation, he worked six weeks in a Royal Canadian Air Force warehouse and earned $35. By then, his father was working for CN Railroads. Unlike Joe Little Sr. who hitchhiked across Canada on boxcars, Steeves got a train pass that took him to Calgary.

His first Calgary job of delivering milk is what Steeves claimed got him into the oil industry. He noted that his customers in the oil industry were a lot smarter and less debt-ridden. So in February 1945, when United Geophysical came to town, Steeves joined one of their earlier crews and started off as a juggie. Roy Lindseth was also hired the same day as a driller 's helper. His first stint was in the Foothills at Grease Creek prior to being transferred down to Wyoming.

Once his American work visa expired, he was sent down to Venezuela where he celebrated his 19th birthday. "That was like going to the end of the world," recalls Steeves.

Venezuela was quite a poor country and infrastructure was not well developed. Steeves worked on a field crew as an observer in the jungles. While there were only six ex-patriates on the crew, there were another 350 locals hired to cut trail for the group. For his first night in a remote jungle location at a fly camp, a dozen fire ants crawled over him and woke him suddenly with three bites. Still, a minor incident compared to what he would yet encounter.

After six months in Venezuela, Steeves was transferred to Sabanalarga, a Colombian town of about 25,000 persons. The only building of significance was the church. Post and pole adobe thatched roofs dominated the landscape. Mules carried the seismic crew's equipment. In fact, 120 mules were required to support the crew of 200 persons. Steeves laughs at the thought that they only ran 12 channels, when today, 1,000 to 2,000 would be the norm. He lived in the town for two years, "Being Single, a gringo and perceived to be rich, we were invited to many social functions, by families with eligible daughters. That was a nice way of getting to know the family, learn the language and become immersed in their culture. In the towns, there was rigid social code, a three hundred-year hold over from the Spanish tradition. You were chaperoned everywhere, even to open-aired theatres."

The next South American assignment took Steeves from the Colombian coast 1200 kilometres south to the drier grasslands. The crew moved by a caravan of trucks, were tormented by rains and road washouts as they zigzagged along mountainous escarpments. They crossed the Andes three times. It took 40 days to cover 1200 km. At camp in the grasslands during a lightening storm, five helpers were killed. Returning from their funeral, another 14 persons died when one truck flipped over.

The South American revolution heated up in early 1948. The day before rebels attempted a coup d 'etat, Steeves had traveled upstream on a river barge which moved seismic vehicles. He stayed overnight at a ranch operated by a man known to have available firearms. In the middle of the night, rebels invaded the ranch. The owner of the ranch eventually persuaded the rebels to leave, after giving them broken firearms. Still, not all was clear. Steeves awoken suddenly the following morning by the sound of a gun thrown at him for self-defense. The gun slid under the mosquito netting into his bed.

In May 1948, Steeves took a two-month holiday and returned to work in Venezuela for another two years. During this time, he proudly acquired his pilot's license, but never used it. The Venezuelan buzzards seemed to be almost as large as the piper J3 aircraft that he flew.

By the time Steeves left South America in 1950, he had acquired a well-rounded field education on all aspects of geophysical field work for the technology at that time. He returned to Canada and completed one year of electronics at Toronto's Ryerson Institute of Technology. Then he came back to Calgary a year later to work for United Geophysical.

In September 1952, he married his wife Francis. Three months later, they found themselves in Venezuela. In April 1953, Steeves was transferred to Denver City, Texas where son Sheldon was born. Sheldon has since grown up to study geology and become Chief Operating Officer and Senior Vice-President at Renaissance Energy. By the end of that year, the Steeves family returned to Canada.

In 1954, Steeves went to work for Chevron as an observer. Field assignments were mainly in western Canada until he was sent down to the United States in 1957, the same year second son Morgan was born in North Dakota. Morgan has since grown up, graduated from SAlT and worked on seismic crews and brokered seismic data in Canada and the United States.

A year later, the family then was moved to Midland, Texas, where Steeves worked for the analog playback centre. During 1958, Steeves moved to Houston to work in the field services section. It is with razor sharp memory that Steeves remembers all of the places he has worked and lived in, although he has no photos of himself in these places.

The nomadic lifestyle was interrupted for a short time. Steeves was based in Houston and supervised the care of seismic field instrumentation and equipment throughout the United States, from Louisiana to California to the Rocky Mountains. At that time, Chevron conducted seismic work in Los Angeles, shot hole as well as vibroseis, working under high voltage transmission lines, along railroads, new freeway easements and residential streets. These circumstances provided many challenges.

In 1959, the family moved back to Calgary. Steeves embraced the digital age at work, "It was a lot of fun. 1was involved with helping the computer geeks unravel the many compatibility problems associated with early digital field recording and main frame processing." Chevron began conducting quality control checks worldwide and Steeves was back accumulating further frequent flyer points.

In 1970, in addition to his domestic field service duties, Steeves was loaned to Chevron's international department for technical services. "Literally, they tell you today that you are leaving tomorrow, you are to work from two weeks to two months for field service assignments. Your shots and your passport were always up to-date."

Steeves worked for Chevron in Indonesia, Japan, Singapore, Australia, Southwest Africa (now Nanimbia), Senegal, Sudan, Senegal, Morocco, Portugal, East China Sea, Gulf of Alaska, in the Arctic and East Coast of Canada. He typically averaged between 90 to 150 days a day out of the country.

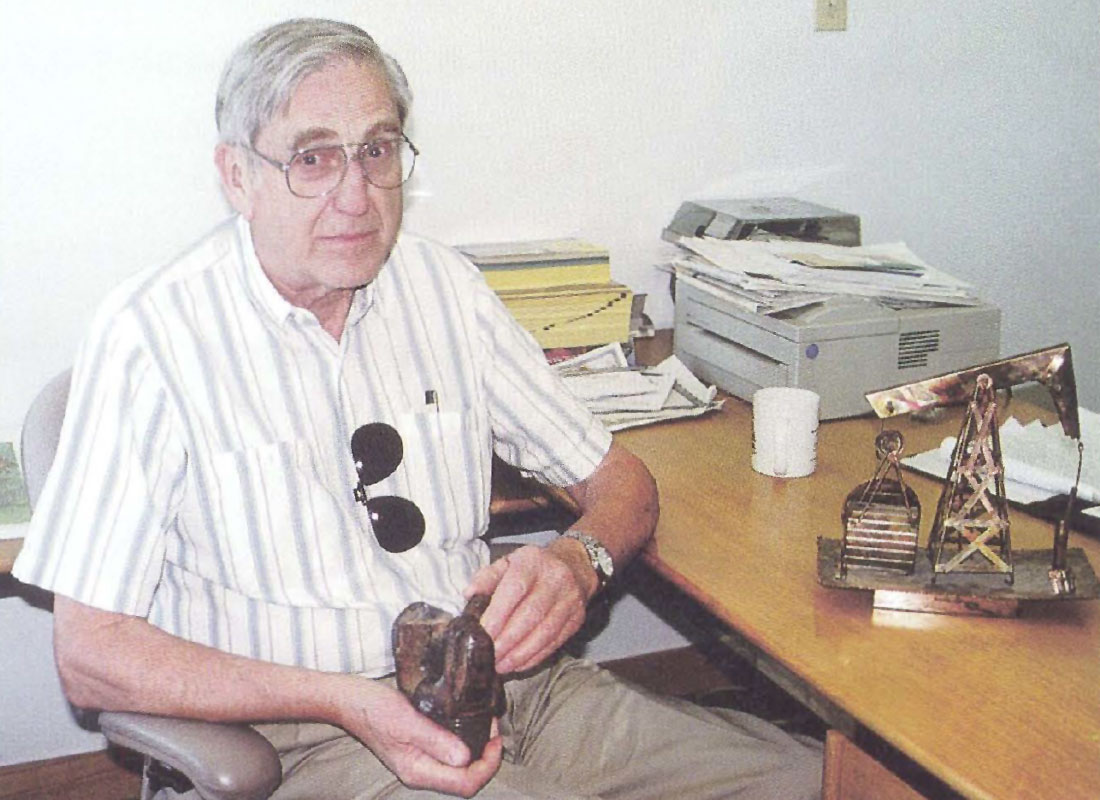

After retiring from Chevron in 1987, Steeves re-activated Tecalta, a family company, which was originally started when the children were teenagers. "It's a nice little basement company," beams Steeves, who is the Canadian representative for the Pelton Company from Ponca City of Oklahoma. With this job supplying companies with vibrator control electronic GPS equipment and Blasters, he gets to combine his hobbies of computers, woodwork and metalwork.

Currently, an active volunteer with the Kerby Centre, his photo was splashed across the front cover of this past August's Kerby News. Having served on the CSEG Committee which produced the 1980's book, Traces in Time, Steeves fancies the idea of writing about his life experiences. But he is in no rush, "The geophysics business is such a fun business. No two days are the same. I enjoyed field services. It was always a challenge, there was always problem and it was a nice feeling to solve it."

Share This Column