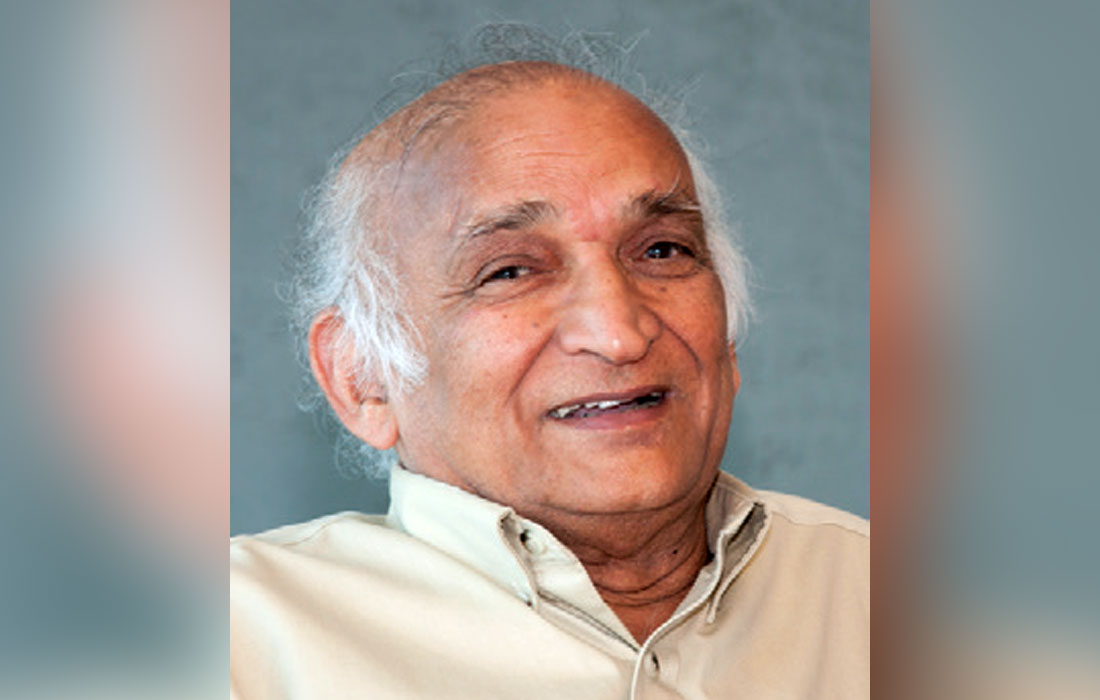

Sudhir Jain is a distinguished geophysicist who was very active in Calgary during the 1970s and 1980s. He was a prolific researcher, writer and a communicator, and one can find several of his papers published in the Canadian Journal of Exploration Geophysics during that time. His early Ph.D. research work at University of Liverpool fetched him the prestigious EAEG Van Weelden award in 1966, a recognition for a “Young Professional” for “highly significant contribution one or more disciplines”. Later, he got the opportunity to work with Milo Backus and Bill Schneider during his stint with GSI in Dallas.

After his arrival in Calgary in 1974, Sudhir’s areas of geophysical interest included seismic migration, AVO and potential field methods, wherein he was always trying to apply newer ideas and solutions to processing and interpretive problems in Western Canada. His vision, sense of practicality and determination enabled him to both make useful technical contributions, and receive recognition as well. Sudhir received the CSEG Meritorious Service award in 1980 and the CSEG Honourary Membership award in 1989.

Upon reading the recent TTI info (September 2014 issue of the RECORDER) about the book launch for Sudhir’s first novel, Penny Colton invited him to sit down with Satinder Chopra for an interview to relay his contributions and experiences from the early years of geophysics in the CSEG community to the RECORDER readers. The telling may be of interest to both the folks who remember Sudhir’s early contributions, and those who are just starting a career in geophysics.

Tell us about your educational background and your work experience and what you are engaged in doing these days?

As a kid I was made to believe that my destiny was to be a doctor. But the idea of cutting a frog, albeit a dead one, was abhorrent to me and I decided, much to the disappointment of my family, to do Physics and Mathematics instead. When I applied for admission to Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) at Kharagpur, a thousand miles from my home town, I chose Geology and Geophysics intending to specialize in Geophysics. At that time, IIT was where every parent wanted their kids to go for studies and by some strange coincidence I was accepted. I was fortunate to have Amalendu Roy teaching us Geophysics. He had a talent for explaining complex ideas and getting his students really involved in what he was teaching. Dr. Roy also supervised my Master’s thesis which was published in Geophysics in 1961. The interesting aspect of this work was that it was a simple form of inversion for potential field and resistivity data. Conventionally, potential field data interpretation is a modeling exercise but Dr. Roy and I showed a simple procedure which could lead to source parameters directly from the data.

I worked for a year collecting gravity-magnetic data in India and then won a scholarship paid by Assam Oil Company but administered by the Government of India to do postgraduate work in England. For reasons I have never understood, High Commission of India in England placed me at the University Of Liverpool. The University had a very good Department of Geology but only one lecturer in Geophysics and hardly any equipment. After some trial and error research, Dr. Wilson, the lecturer, and I settled on the investigation of sediments under the Irish Sea using magnetotelluric method which was being developed by Russians as an exploration tool. My work suggested thick conductive sedimentary rocks north of Wales and between Ireland and the Isle of Man which was not yet known, certainly not at Liverpool. The work resulted in papers in European and British journals culminating in Van Weelden award for 1966 by E.A.E.G.

After graduating from Liverpool, I worked for GSI for a little over four years. Those were the days digital processing was being introduced and GSI were the leaders in the field. They sent me to Dallas for five months of training where I mostly worked in the Research Department with leading lights of the day, Milo Backus and Bill Schneider. GSI had a very good correspondence course program which I joined. I learnt a lot of practical things from these courses. After a little over two years in London I spent another two years with GSI in Libya before switching over to Mobil there. Mobil Libya received a set of seismic processing software from Mobil Canada and I was given the job of installing it. I worked on improving it in various ways to make it more suitable for poor data quality. That was a great learning experience.

After Gaddafi’s revolution in September 1969, oil exploration in Libya came to a standstill. Mobil offered me a couple of transfer possibilities in Europe but I was intent on doing research. I applied to Canada and the U.S. for immigration visa and moved to the U.S. because they were prompt in issuing the papers. Aero Service Corporation in Philadelphia offered me a job to develop interpretation software for aeromagnetic data. That was a great opportunity to broaden the field of geophysical experience. Two and a half years later, Digitech enticed me with the big title of Research Manager and a decent raise and we moved to Calgary in the first week of February 1974. After two years, I decided to set up my own shop and Commonwealth Geophysical was born. I developed proprietary inversion software for seismic, gravity and magnetic data. Some companies liked what I was doing and the company expanded to as many as ten technical people doing inversion related processing and interpretation in all branches of geophysical prospecting.

What am I doing these days? Not much or a lot. Depends on how you look at it. Some of my friends have entrusted me with their retirement funds. This is not much work in itself but I do take this responsibility seriously; it is my dear friends’ old age I am looking after. More of my time is spent on writing and what goes with writing – editing and reediting the work, sending it to prospective publishers, promoting the books. Writing itself has many aspects – generation of ideas on what to write, maturation of these ideas, what form is appropriate for the subject, not the least who should be the narrator. Weeks and months can go by before the germ of an idea gets to the point when you can hit the keyboard. Even then, you can be half way through when you find it is not working and you start again. Every once in a while, particularly with essays, you complete the piece and decide to forget about it because it no longer makes sense to you. Good thing is that while you are writing a particular essay or a story, other ideas are crisscrossing the brain and hopefully one will be ready when the current project is finished.

How would you describe yourself in five words?

Hardworking, confident, trustworthy, calm under pressure, ambitious.

What is it you loved about our industry, where you remained active for a long time?

In my forty years in Geophysics, I did not come across one instance of prejudice, whether for colour, nationality or religion. The people hired you if you could do the work they needed done and if it did not work out your personal relationship stayed the same as before. There was never any problem with being paid for the work. Most geophysicists I came across loved what they were doing. They had strong opinions but kept the ears and minds open. Working atmosphere was as good as one could ever wish for.

Who are the geophysicists of your time that you admired for their work?

First of all, I was very lucky in the geophysicists and systems analysts who agreed to work at Commonwealth and I derive great satisfaction from what we achieved together. As I said earlier, I admired so many people I could write a book about them. Maybe I will someday. But for now, Rob Stewart is the most brilliant person I have come across anywhere, although I never had the good fortune to work with him. I admired Easton Wren for his ready grasp of a new idea and the ability to explain it better than the person whose idea it was. Peter Savage was perhaps the best Exploration Manager I worked with. He knew what he wanted from his people and his consultants and how to get it. Lorne Kelsch was a Chief Geophysicist in a class by himself. He knew what data he needed, how to use it most effectively, listened to new ideas, and supported them but only when they made sense to him.

Everyone has a driving goal in life. What has it been for you?

say this, neither with pride nor humility but for the sake of honesty. I was driven by an ambition to be a major success, to set an example to others with my achievements. I realized much too late that I did not have the innate talent or the extraordinary ability to achieve this and it has been very hard to reconcile my very modest achievements relative to my great ambition.

I have come across many of your papers written and published in the late 1970s and the 1980s. You were active in delivering talks as well. Tell us about those experiences? Do you have some memorable incidents from your professional successes?

I enjoyed writing papers and delivering talks since my postgraduate student days. I was unduly nervous and therefore mumbled a lot in my first few presentations. Then an old hand, I did not even know him, told me something like “You know more than anyone in the audience and there is nothing to be nervous about. So you can speak clearly and confidently and every one would be better off.” I took the advice and it helped my writing as well.

I like to think that although the material I presented was related to the services I offered, my presentations were not marketing gimmicks because I tried to point out what could not be done as much as what could be achieved by the processes. A proof is that it was rare indeed when someone contacted me for my services after a presentation. I never deliberately oversold any of my services and did not offer them when they were not likely to work. Of course there were times they did not work after my recommendation but things don’t often turn out the way you expect them to.

The papers and talks to CSEG, SEG, EAEG, AGU and luncheons made me friends in the geophysical research community and the exchange of ideas was very helpful to me, perhaps to them too. One memorable incident, from a personal point of view, was after my talk on Magnetotelluric methods in Madrid in 1965. A research chief in a major oil company in California approached me. In my ignorance I brushed the gentleman aside. I have often felt a tinge of regret over that folly.

What problems in geophysics particularly fascinated you in your hay days and you pursued them vigorously?

In sixties the properties of the sediments were deduced by modeling. My work for the Master’s thesis introduced me to deriving the properties directly by analyzing the data. This process got to be known as inversion and most of my development work was related to it. True Amplitude Recovery introduced in the early seventies was necessary for meaningful inversion and that is what attracted me to it when I joined Digitech. Inter-bed multiples introduced confusion for inversion in areas of Devonian reefs and it induced me to work on their attenuation. Estimating velocity fluctuations from the amplitudes and integrating them with low-frequency velocity component from normal move-out was my main occupation throughout my career in Canada and, I must say, the main source of my family’s financial wellbeing. I developed software for magnetic and gravity data inversion and used it successfully. It was a life saver when seismic business was slow.

Do you still read the CSEG RECORDER?

I stopped receiving the RECORDER a few years ago due to the confusion about my address. The problem has now been rectified and I can stay abreast of the developments in the profession.

Give us a day in the life of Sudhir Jain in say the 1980s and 2014?

1980s were difficult years for our family and there was not a day (or year) that was typical. Our daughters were 12, 9 and 2 in 1980. Evelyn, my wife, was taking science undergraduate courses as a precursor to five years of medical training which she completed in 1989. My services were in great demand at that time. I got up at 5:30 and got to work downtown around seven. In early 1980s I had Dan Petch working with me. We had two rooms on the eighth floor of the building Digitech was in. I used Digitech’s computer facilities for an hourly fee. I also had an agreement with PanCanadian to spend twenty five to thirty hours a week on their jobs in the office they had provided in their building in Palliser Square. I would work from seven till nine on other clients’ jobs, help data processors of two companies who used my software (if the help was needed) and then walk over to Palliser Square. I would work there till four or so, walk back to my other office to work for an hour and get home by six. Evelyn insisted that we had a dinner together as a family and our girls still cherish that rule. I spent the evening helping in the kitchen and children’s activities, putting the girls to bed and then work on the software development or publication project for a couple of hours. It was always a very full but a very satisfying day. The routine changed somewhat in the late eighties when some more professionals joined me but workload was always about the same. I must say here that Evelyn was absolutely amazing in those years carrying the tremendous workload of a medical student as well as managing a family with three growing daughters at various stages of schooling. Looking back I am amazed that we pulled through it all in one piece.

2014 is very different. Now there is nothing that must be done, there are no deadlines and the daughters have moved away, two to Vancouver, one to San Francisco. I still get up around 5:30. There are exercises prescribed by physiotherapists over the years which take an hour every morning and the day goes by in a little reading, some writing, some work on investments and of course the necessary jobs around the house. The people our age have one of the four major preoccupations: receiving medical attention, tending grandchildren, cruises and other travels and finally golf or bridge. Evelyn and I have none of these things to occupy us except for odd weeks our grandchildren visit us from their home in San Francisco. But both of us like reading, Evelyn still does lactation consulting three mornings a week. She is an avid gardener, a wonderful cook and an excellent editor of what I write. Most of the time, we do what we enjoy much of the day blessed with good health and the company of great people who have kindly chosen us as their friends.

You have had a full cycle/life. Is there anything else you wish you had?

I am finally reconciled to the life I had. I do wish I had done more voluntary work with CSEG when I was consulting and had been able to support cultural organizations to the level justified by the joy they provided me. I am grateful for the support I have received all along from the colleagues and the family although my temperament, and you could call it lack of social graces, must have made it very hard for them.

How is it you gradually put a stop to practicing geophysics?

I realized that I was not able to focus on the research side of my work and that had been the sustaining part for me. About that time I got involved in a couple of exploration projects which could be in conflict with the consulting business. In what turned out to be a huge misjudgment, I decided to pursue the exploration projects and ‘retired’ from geophysics. Both projects bit the dust and caused me much grief.

How did you reconcile your very busy career in Geophysics with the needs of your family?

I worked long hours but I always placed the family first. I made time to watch the concerts and games of our girls, did my chores at home and took time off from office when I was needed. However, I worked late in the evenings and over the weekends, went to the office early, worked without a break all day and believe it or not, enjoyed every moment of it. I was doing what I loved; doing it for the woman and the girls I adored, my work was appreciated by my clients who retained me year after year. I was happy and, dare I say, fulfilled.

How did your family help or hinder with what you wished to do in your careers?

My wife was always supportive in my career. She moved to three different countries in nine years leaving friends and family behind. She has this great capacity to make friends for life which helped us settle in new places. She does not find faults in me just to put me in my place but does correct me when it would be helpful. She edits all my writing and makes suggestions for improvements. She helped me in promotion of my business in old days and promotes my books now, even joining me in book readings. Most of all, she has been a wonderful mother even when she was a medical student and a resident. My daughters make constructive comments on my writing and these have helped my books, particularly the novel.

I have had an inner peace in my family relationship and that has freed all my energy for the works I undertook. What more can a man wish.

Once you stopped practicing geophysics, you turned to writing letters on a variety of subjects and published in newspapers. Tell us how this happened.

I am, as a character in one story describes himself, like a wide but a shallow lake. I have an opinion about everything under the sun. That may not be bad in itself, but I also think that others should be told of my reaction to the events occurring at any time anywhere. What better way to do it than send a letter to the newspapers. For whatever reason, editors liked my fulminations and published them. That encouraged me to write more and send them to a wider field. Fortunately, it took me just a few minutes to do it so other activities were not impacted.

That brings me to another question: Einstein once said ‘If you cannot explain something simply, you don’t understand it well’. For someone like you, who is writing fiction, it is telling enough that you are able to simplify and describe well. You could have contributed well in geophysics. Why did you not continue to write in geophysics?

That is an excellent question and a very difficult one to answer. I did try to do it in some RECORDER articles in the late nineties and some people liked these articles. However, classical music and literature were my pastime since childhood. I wrote a story on the love of young Gustav Mahler, a German composer (1860 – 1911) and an older married woman. I also wrote some about the events in my daily life. I could write these stories quickly, in a few hours spread over a few days. These were popular among literate friends who encouraged me to write more. On the other hand, geophysical articles require considerable reading, a period of gestation and then very careful writing and editing. Technical writing needs concentration and uninterrupted time periods. My kind of fiction needs very little research, it is a combination of what I remember and what I can imagine. No one is going to complain about accuracy and any learning from it is incidental. To make it short, it was easier to write for readers’ amusement than writing for information and I chose the easy path.

What is the central theme in your recently published book entitled ‘Princess of Aminabad: An Ordinary Life’?

The central theme is how the changing social and political environment of twentieth century India impacted on the life of an ordinary woman and how her actions accelerated these changes. The broad structure of the novel is loosely based on the life of my mother who lived through most of the twentieth century. I thought that weaving real events from her life with social and political changes going on around her was a good base for a novel. Of course, the life events had to be modified and many new ones invented. It is not a biography, not even a bio-novel because so much of it is my imagination.

Your first book entitled ‘Isolde’s Dream and Other Stories’ was published in 2007. What was that about?

It is a collection of two types of stories. Two bookend stories are fictionalized accounts of love affairs. In the title story Richard Wagner, German opera composer (1813 – 1883) falls in love with the wife of his patron when he was composing the opera on an illicit love affair between a courtier and the queen. The first story is the tragic story of composer Mahler and Marion von Weber I referred to earlier. It is the most moving heart-on-the-sleeve story you are likely to read. I can’t believe I wrote it. I have always had a close affinity with Mahler’s music and Wagner’s operas and people tell me that this comes out in the stories.

Most of the other stories are sourced in events from my life and are told with self-deprecating humour. These are short stories you can read before going to sleep without worrying about nasty dreams. There is a contemplative essay on the time I got lost for three days in the forest near Prince George which readers won’t let me forget. It was a popular book and the library copies are more often out than on the shelves.

We’ll also like to hear about the book you published in 2012, ‘Pages from an Immigrant’s Diary’.

These are the stories of immigrant experience, some funny, some serious and not necessarily my own. After leaving India I lived in three other countries for extended periods before settling in Canada. The stories are based on events from these countries, from student days to some recent experiences.

Last chapter of the book is a series of essays, some published previously in the media, about what I learned in life. I don’t believe that one necessarily gains wisdom with age but being a thinking type, there could be some things I learnt that may be of interest to the readers. A former geophysicist who read the book found this section more interesting than the rest, but he was an exception.

Having achieved so much in terms of name and fame, what is it that motivates you now?

As for the name and fame, I concluded a while ago that I did not achieve the level of success I always dreamed about but it was because I overestimated my talent and skill level and it was too late now to do anything about it. At my age I have at best a few healthy years left. I want to spend these in doing my bit to help my family and community and spend my spare time in writing amusing stories or instructive essays which will be positive experiences for the readers. Motivation is really to do the least harm and as much good as I can do for those around me.

With a life-long experience behind you and the fact that you are a writer, we could ask you a couple of philosophical questions: Some people opine that experts are more persuasive when they are less certain. Would you agree? Could you elaborate on this?

I have learnt that I am absolutely certain only when I am wrong. I am ashamed to think how many times I became angry and told off colleagues or family members and later found that it was my mistake. To be persuasive one must be less certain because there is a give and take in discussion then. No one likes orders. The best way to persuade people to do what you think should be done is to convince them that it was what they always wanted to do. You can only do that when you are patient and working out the solution together, even though only the final phases of it.

You may be in a situation where you think it seems right, but it doesn’t feel right. What would you do in such a situation?

I almost always go with feeling because it is my subconscious telling me something that is based on what I experienced but do not want to face. Thought and feel are in harmony only when logic is consistent with experience.

What differences did you notice when you turned 30 years, 40 years, 50 years, and 60 years old, and then at present? As an example, some people think 30s allowed them to experiment with options, 40s gave them time for self-introspection or naughty at 40, and so on. Your comments?

At the age of 30 I was living in Libya and had a one year old daughter. Everything was rosy and I looked forward to a great career in geophysics and a happy family life. Ten years later, I had moved to Canada via USA, was consulting and my seismic inversion process called Soniseis had taken off. We had three daughters now and we liked our life in Calgary. The expectations were being realized and I thought Commonwealth Geophysical would grow into a major operation. But I had to temper my growth plans for family reasons although I developed some very useful software, published some good papers and the company grew to ten or twelve people during the decade. My wife completed her medical training the year after I turned fifty and started her medical practice which was very successful. Introspection came at this stage and I began writing, mostly on classical music and religion, to clear my thinking. We built his and her office buildings on the same lot, one for the practice of geophysics and the other for the practice of medicine. When sixty, I got involved in two projects, one for oil exploration and the other for iron ore. These were at least partly instrumental in my retiring from geophysics. I worked hard on these but they both failed and embarrassed me no end. I began writing letters to the media and essays and stories a couple of years later. My first publication was around this time, an essay on atheism.

Life now is very different. Our daughters have grown into fine women with successful careers. My wife and I do worry about our two young granddaughters who have some problems. Other than that, I have all I need and could possibly need for the rest of my life. I am reconciled to the past, content in the present and prepared for the future.

What would be your message for youngsters who have joined our industry recently?

You are in a profession where the level of uncertainty is high. It is much better than a blind person throwing darts but if you hit the bull’s eye every time, even most of the time, something is wrong. There will be pieces of puzzle missing. But the decision has to be made, to drill or not to drill before land expiry by an Exploration Manager, or a reef or a multiple by the geophysicist. But you can’t be sloppy in a situation like this. Do the best you can do with all the data available in the given time frame. The rest is in the hands of God if you are religious or the game of statistical probability if you are a non-believer.

Share This Interview